Dr. Thomas C. Poulter served as second in command of Admiral Byrd's

Antarctic Expedition II (1933-35). During this expedition, Byrd nearly lost

his life when he was isolated by the weather at a forward base. While the

Admiral was only 123 miles away, inhospitable conditions foiled several rescue

attempts until one finally succeeded. Following this incident, Dr. Poulter

began to envision a vehicle that was specially adapted to the Antarctic

environment -- a "Snow Cruiser".

After returning from Antarctica, Dr. Poulter took the position of

scientific director of the Research Foundation of the Armour Institute of

Technology in Chicago, Illinois. He convinced the Research Foundation to

embark on design work for his Snow Cruiser. Under his direction, the staff of

the Research Foundation worked on the design for approximately two years

(1937-39).

Learning that the government was planning another Antarctic expedition to

be headed by Admiral Byrd, Pouter presented the completed plans for the Snow

Cruiser to expedition officials. Getting a favorable response and $150,000 in

upfront financing, construction work commenced on the Cruiser at the Pullman

Company in Chicago in August 1939. The vehicle was completed in October. The

only problem left was how to transport it to Boston where the Antarctic

expedition ship lay berthed.

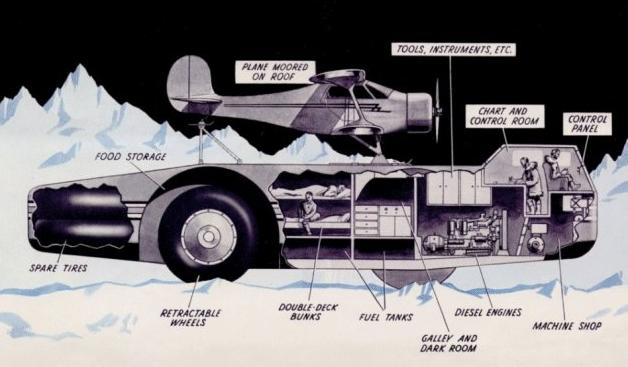

The vehicle was a behemoth any way you looked at it. It stretched almost 56

feet long with a wheelbase of 20 feet, a width of almost 20 feet and a height

of 16 feet with its cab fully "extended" on its hydraulic lift cylinders. It

weighed more than 30 tons fully loaded with a year’s supply of fuel and

provisions for its four-man crew. With a range of more than 5000 miles, it ran

on 10-foot diameter Goodyear pneumatic tires. Inside were living and sleeping

quarters, a welding and machine shop, a darkroom, a galley, instrument room

and radio room. Its engine room contained two 112 kW diesel engines, two 75 kW

electric traction generators, and two hydraulic pumps. The fuel tanks held

9500 liters of diesel fuel, 3800 liters of aviation fuel and 2800 liters of

white gasoline.

Why the aviation fuel? Because the Snow Cruiser was also designed to carry

a Beech reconnaissance aircraft on its roof!

Four-wheel steering allowed it to turn within a radius of 30 feet. Using

hydraulic jacks, the Cruiser could cross 15-foot crevasses, one of the most

dangerous aspects of traveling across Antarctica. At a crevasse, the driver

could retract the cruiser’s front wheels, push the body across with the rear,

then reverse the process and pull the Cruiser across with the lowered front

wheels.

Incredibly, the vehicle was driven from Chicago to Boston across regular

public roads. On its first trial run of 13 miles over smoothly paved streets

in Chicago, the cruiser managed to make only 10 MPH, less than its top speed

which was supposed to be 25 MPH. It was difficult to steer, and had trouble

turning corners. It stopped suddenly, completely and without explanation

twice, and got stuck for 15 minutes under a viaduct.

But there was no time for re-engineering, as Byrd's expeditionary vessel

was running on a tight schedule. The trip to Boston began on the next day. The

cruiser lumbered into Gary, Indiana at speeds up to 20 MPH, and was taken off

the main road for a brief test in climbing "snowdrifts." In this case the

snowdrift was a sand dune 19 feet high. Six tries failed, but on the seventh

the cruiser went over the top with the help of a 50-foot running start.

On the road to Boston again, the cruiser had a minor collision with a truck

in Columbia City, Indiana. Next day it struck the corner of a bridge near

Gomer, Ohio, and careened downhill into Pine Run, a 10-foot stream. There, in

the middle of Mrs. Cleo Watkin's cow pasture, it lay helpless with its nose

buried in a mud bank. After 70 hours of rescue work, the cruiser was hauled

back on the road. Undaunted, it started off for Boston and the Antarctic once

more.

In Akron, the crew picked up two spare tires from Goodyear. On November 4,

the Cruiser reached Erie, Pa., where General Electric replaced two motors that

were damaged in Ohio. They had hoped to leave two days later, but difficulty

in installing the motors delayed them. While attempting to sneak out of

the shop early to beat the crowds, an oil line broke.

Finally, on November 12, the Snow Cruiser limped up to the North Star

at Boston Army Wharf. With the Cruiser safely lashed to her deck, the ship put

out to sea three days later. On January 12 the ship reached its Antarctic

anchorage at the Bay of Whales. To unload the Snow Cruiser from her deck, a

large ramp was constructed of heavy timber. Halfway down the ramp the timbers

began to break. Dr. Poulter quickly gave the Cruiser full throttle and she

lurched from the ramp to the safety of the ice.

The Snow Cruiser barely made it the two miles to the base, Little America

III. The machine was too heavy to cruise gracefully over the snow. The huge

tires did not provide adequate traction, and there was not enough power to

drive the Cruiser over the chocks of snow that formed in front of the wheels.

Had the crew carried equipment to change the Cruiser’s gear ratio the problem

may have been fixed – power had been sacrificed for speed. Far from its plan

for driving to the Pole, the Cruiser never left the bay ice of the Ross Ice

Shelf.

The Snow Cruiser was parked in a shelter made of snow blocks and canvas.

Several men used the otherwise useless vehicle as sleeping quarters. The

Cruiser’s four-man team and its Beechcraft plane joined the rest of Byrd’s

expedition.

During the winter of 1940, one final attempt was made to revive Dr.

Poulter’s creation. It was hoped that the winter cold had hardened the ice

enough to support its weight. For awhile it actually moved along the ice, but

a blizzard soon blew in and the surface was again too soft. The Snow Cruiser

was abandoned and written off as useless.

By the early 1960s the ice sheet supporting the Snow Cruiser had migrated

seaward and broken off. By all accounts, Dr. Poulter’s hopeful but impractical

invention now lies at the bottom of the Ross Sea. There will never be another

vehicle like her.

That makes me sad. The conception of such a wondrous machine could

only have happened in an era when men believed that all things were possible,

that our unbridled destiny was in reach of those who were bold enough to

envision it and daring enough to grasp it. Now we deal with modern

concepts of "risk management" and the naysaying of peckish accountants; we

study and test endlessly without actually doing anything; our

civilization and its future history seems clouded by pessimism and fear of

loss. There is no longer any room for heroic failure. And our

culture is the less for it.

Back to Lost Articles...

http://www.joeld.net/snowcruiser/snowcruiser.html

Thanks to my friend John Knoph for turning me on to this

wonderful item!